I'll also just quickly mention that this is my 100th post.

Archbishop Wuerl's homily:

Brothers and Sisters in the Lord,

It is a privilege for me to join each of you at this 53rd annual Red Mass sponsored by the John Carroll Society as part of a noble tradition in our nation’s capital of invoking the blessing of God’s Holy Spirit on all who are engaged in the service of the law, especially the members of the judiciary.

Recently I received a beautiful plant rooted in a very attractive container with gorgeous flowers mixed throughout the arrangement. Within a few short days, however, even though I took great care of it, some of the flowers began to fade. It was only after I removed one of the withered flowers that I made the startling discovery that not all of the flowers were attached to the plant and rooted in the soil, but instead simply were placed in little plastic containers. As the flowers were not part of the plant and not rooted in the soil, they had no source of nourishment and died.

A beautiful flower in an isolated container is much like the branch that Jesus speaks about in today’s Gospel text from St. John, the branch that gets cut off, detached from, isolated from the vine. Such a branch cannot bear much fruit—certainly not for long.

Whatever image we use, the lesson is the same. We cannot be cut off from our rootedness. We cannot become isolated from our connectedness and expect to flourish. As a people, we have a need to be part of a living unity with roots and a lived experience, with a history and, therefore, a future. Our lives as individuals and as a society are diminished to the extent that we allow ourselves to be cut off or disconnected from that which identifies and nurtures us. Branches live and bear fruit only insofar as they are attached to the vine.

No one person, no part of our society, no people can become isolated, cut off from its history, from its defining experiences of life, from its highest aspirations, from the lessons of faith and the inspiration of religion—from the very “soil” that sustains life—and still expect to grow and flourish. Faith convictions, moral values and defining religious experiences of life sustain the vitality of the whole society. We never stand alone, disconnected, uprooted, at least not for long without withering.

A profound part of the human experience is the search for truth and connectedness, and the development of human wisdom that includes the recognition of God, an appreciation of religious experience in human history and life, and the special truth that is divinely revealed religious truth.

Science linked to religiously grounded ethics, art expressive of spirituality, technology reflective of human values, positive civil law rooted in the natural moral order are all branches connected to the vine.

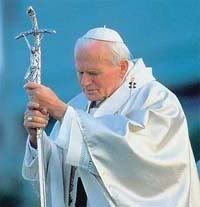

A healthy and vital society respects the wisdom of God made known to us through the gift of creation and the blessing of revelation. We not only need God’s guidance, but we are created in such a way that we yearn for its light and direction. Pope John Paul II in his encyclical Fides et Ratio reminds us: “...God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth—in a word, to know himself—so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to the fullness of truth about themselves.” (Intro., Fides et Ratio)

One reason we gather today in prayer for the outpouring of the gifts of the Holy Spirit is our realization that it is the wisdom of God that fills up what is lacking in our own limited knowledge and understanding. Connected to the vine, we access the richness of God’s word directing our human experience under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Cut off from the vine, we have only ourselves.

At times our society, like many contemporary cultures heavily nurtured in a secular vision that draws its inspiration elsewhere, can be tempted to think that we are sufficient unto ourselves in grappling with and answering the great human questions of every generation in every age: how shall I live; what is the meaning and, therefore, the value of life; how should we relate to each other; what are our obligations to one another?

The assertion by some that the secular voice alone should speak to the ordering of society and its public policy, that it alone can speak to the needs of the human condition, is being increasingly challenged. Looking around, I see many young men and women who, in such increasing numbers, are looking for spiritual values, a sense of rootedness and hope for the future. In spite of all the options and challenges from the secular world competing for the allegiance of human hearts, the quiet, soft and gentle voice of the Spirit has not been stilled.

Just as we are told in the first reading today that the Spirit of God was shared with some of the elders so, too, today we have a sense that that Spirit continues to be shared. The resurgence of spiritual renewal in its many forms bears testimony to the atavistic need to be connected to the vine and rooted in the soil of our faith experience.

As Jesus assures us in today’s Gospel: “Just as a branch cannot bear fruit on its own unless it remains on the vine, so neither can you unless you remain in me.” The revelation of the mystery of God-with-us is not incidental to that human experience. It gives light and direction to the struggle we call the human condition. Religious faith and faith-based values are not peripheral to the human enterprise. Our history, the history of mankind, is told in part in terms of our search for and response to the wisdom of God.

Religious faith has long been a cornerstone of the American experience. From the Mayflower Compact, which begins “In the name of God, Amen,” to our Declaration of Independence, we hear loud echoes of our faith in God. It finds expression in our deep-seated conviction that we have unalienable rights from “Nature and Nature’s God.”

Thomas Jefferson stated that the ideals and ideas that he set forth in the Declaration of Independence were not original with him, but were the common opinion of his day. In a letter dated May 8, 1825, to Henry Lee, former governor of Virginia, Jefferson writes that the Declaration of Independence is “intended to be an expression of the American mind and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit.”

George Washington, after whom this city is named, was not the first, but perhaps was the most prominent, American political figure to highlight the vital part religion must play in the well-being of the nation. His often-quoted Farewell Address reminds us that we cannot expect national prosperity without morality, and morality cannot be sustained without religious principles.

Morality and ethical considerations cannot be divorced from their religious antecedents. What we do and how we act, our morals and ethics, follow on what we believe. The religious convictions of a people sustain their moral decisions.

What is religion’s place in public life? As our Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, tells us in his first encyclical letter, “Deus Caritas Est” (God Is Love): “[f]or her part, the Church, as the social expression of Christian faith, has a proper independence and is structured on the basis of her faith as a community which the State must recognize. The two spheres are distinct, yet always interrelated” (DCE 28). Politics and faith are mingled because believers are also citizens. Both Church and state are home for the same people.

The place of religion and religious conviction in public life is precisely to sustain those values that make possible a common good that is more than just temporary political expediency. Without a value system rooted in morality and ethical integrity, there is the very real danger that human choices will be motivated solely by personal convenience and gain.

To speak out against racial discrimination, social injustice or threats to the dignity of life is not to force values upon society, but rather to call our society to its own, long-accepted, moral principles and commitment to defend basic human rights, which is the function of law.

Not only did Thomas Jefferson subscribe to the proposition that all are created equal, but his writings indicate that he extended the logic of that statement. All people are obliged to a code of morality that rests on the very human nature which is the foundation for our human dignity and equality. Jefferson recognizes no distinction between public and private morality. In a letter dated August 28, 1789, to James Madison, who later became the fourth president of our country, Jefferson wrote: “I know but one code of morality for all, whether acting singly or collectively.”

Perhaps nowhere is the relationship of values, religious faith, public policy and the application of the law more deeply rooted in its historic expression than here in our nation’s capital. Here is the place where our first president, George Washington, and the first Catholic bishop in our country, John Carroll, recognized so very early on in the life of our country the need to respect, honor and support the understanding that the goals of governance and the expression of faith-based morality mingle and overlap. At the same time, each was respectful of the prerogatives of the other, and both were mindful that all the voices needed to be heard.

In the end, the goal of public policy, and its application and interpretation, must be not what we can do but what we ought to do; not what we have the ability to achieve, but what in our hearts, in our conscience and in our souls we know we must do.

As believers, our hope for a better world is rooted in our faith that God will help us make this happen. Faith is the source of our perennial optimism and our social activism and involvement. If we work and work hard enough, God will be with us to bring about that world of peace, justice, understanding, wisdom, kindness, respect and love that we call His kingdom coming to be on earth.

Our prayer today is that our American democratic society will continue to be a flowering plant connected to the vine with roots sunk deep into the rich soil of our national identity, spiritual experience and faith convictions. May our religious faith, as a foundational part of our national experience, continue to nurture and sustain each branch of our society so that by its very connectedness to the vine it can blossom and flourish.

Thank you.

Source

2 comments:

Thanks for posting this. It didn't occur to me that it would be Archbishop Wuerl giving the homily.

Congrats on your 100th post!!

Congratulations on your 100th post. You offer an interesting blog.

Karen

Post a Comment